Last month Dr Sophie Ratcliffe, English Tutor and Fellow at LMH, was awarded an Oxford University Public Engagement award for her project Unsilencing the Library. Based on the finding of a 19th century shelf of imitation books at Compton Verney in Warwickshire, the project brings together the history of women’s rights, the curating efforts of a diverse group and the life and story of a fascinating woman. In this interview, Dr Ratcliffe tells us more about this project and how it fits with her wider research interests.

What are you research interests?

I’m fascinated by the history of reading and how books shape the way we feel. I’m interested in what libraries do. Can a library have an effect just by being there, even if nobody opens the books? For example, I recently went down to look at the archives of the East London Children’s Hospital Library, which was founded in Shadwell in 1868 – an extraordinary place, visited by Dickens. I was looking to find out not just in what was on the shelves, but also in what it means to have a library in a hospital. How does it help people? Does it make a difference?

I’m also really interested the relationship between literature and material culture. I love thinking about books as objects and the things that we do with them. I’ve just written a chapter about this in relation to Dickens for a book called Paraphernalia!. I argue that Dickens was worried about what would happen to his little flimsy serial numbers when they were published, worried they might be destroyed, and that this anxiety is embedded in the texture of his prose. So I guess I’m interested in the after life of books and the life beyond the book.

How did you get involved in the project?

I bumped into Professor Steven Parissien, the director of Compton Verney Art Gallery by chance. On finding out that I worked in 19th century literature, Steven said that they had ‘a women’s library’ from that period, and asked if I’d come and have a look. I decided to visit and walked into an amazing art gallery and museum. Compton Verney was once a grand country house, but by 1993 it was extremely run down. It was beautifully restored with funding from the Peter Moores Foundation. There is an amazing collection of British portraits, a Chinese gallery, and a gallery of folk art. And then there was this lovely, but relatively unrestored, room, known as ‘The Woman’s Library’.

The room has six empty Victorian bookshelves, and something that looks like a bookshelf but really isn’t. It is, in fact, an imitation bookshelf disguising a door. There are book spines, but no books, and it makes the doorway look like one of the shelves in the room. The spines are leather, and tooled with the name of the book and the author. And what’s particularly unusual about the spines is that all the authors are women. This is an incredible artifact, a testament to someone who wanted to say something about equality of the mind, women’s reading, writing and learning. Steven wanted Oxford University’s help to research the room further and also to think about how it should be curated. Given my interest in the life of small things, books, and material culture, this was an amazing opportunity to help to make this small space come alive.

Do you know which books used to be in this room before?

No. We have the library catalogues of Compton Verney (and Compton Verney used to have a big library). However, we don’t know which of the books from that catalogue would have been in this little library room. We know that this room was used by a number of the mistresses of the house, including a woman called Georgiana Verney, the 17th Lady Willoughby de Broke. We are pretty sure that she put up these imitation book spines but we don’t know whether these imitation books were chosen to mirror the real books she kept in the room or perhaps to mirror books in the library as a whole. Many of the books on the imitation spines match the library catalogues, but not all. As researchers, we were obviously hoping to find a letter in the archives saying something like ‘Dear Belinda, I decided to put up an imitation bookshelf, with all my favourite woman authors. Here is a list of them’ ! But alas, we didn’t. So the mystery wasn’t to be solved that way.

Over time, two of the panels of imitation spines had fallen off. And one of the things that Steven wanted us to do was to suggest titles to fill these blank panels. These would then be created by an expert bookbinder. So they asked us (my colleagues Dr Ceri Hunter and Dr Eleanor Lybeck and me) to decide which selection of books should be added to fill the blanks. This was really a glorious gift to a team of researchers - an opportunity to join the dots and finish the story. But it was also a tough call, because it was hard to get a completely definitive sense of what these books are doing together. There’s Mary Shelley, Mary Somerville, Sappho. There’s Elizabeth Barret Browning and Fanny Burney. But there was no Austen and no Brontë. And nothing as radical as, say, Mary Wollestonecraft. Led by Ceri, who is an expert in 19th century women’s reading, we decided that we would select women authors that were in the library catalogues at the time, particularly authors that fell in the trajectory of the collection of books already in the imitation shelf – that is, books about European learning, respectability, polite society. We decided to add Austen to the imitation bookshelf because we know that her books were in the house. As Brontë was not in the catalogues we didn’t add her, and instead filled the other blanks with other writers in the catalogue, such as Aphra Behn, Maria Edgeworth and Charlotte Yonge.

Do you know anything else about Georgiana Verney?

I’m captivated by Georgiana. Local historians Peter and Gill Ashley Smith had found out quite a bit about her already by the time I joined the project. If you’ve ever read those Victorian novels about horrible landlords who keep their tenants in poverty, she’s the complete opposite. Georgiana was known for her ‘open heart and hand’ and the newspapers at the time talk about her generosity and what she was doing for her community. At her funeral, the people in Kineton lined the streets.

Georgiana came to Compton Verney at the age of 28. She probably didn’t expect to be an aristocrat. She was from a military family, and only became Lady Willoughby de Broke due to the complexities of inheritance. She had 7 children, and by 32 was widowed. You might imagine that if this was an Austen novel she might have just spend her life on the sofa in a kind of ineffectual swoon, but she didn’t. She was very active in the local community. She was a keen sheep farmer and breeder and a keen gardener. She built a tramway for the faster transport of iron ore. She helped found literary societies and coffee houses to aid the temperance movement and helped the local school. This was the age of self-improvement, and I think this idea of self-improvement is congruent with what we see in the bookshelf in the women’s library.

She was also interested in wider causes. In 1860-61, Warwickshire and Coventry were experiencing huge hardships due to the collapse of the ribbon industry. The government cut the tax on imported ribbons, so the English ribbon industry was undercut by French ribbon producers. Coventry subsisted almost entirely on the ribbon industry, so many people were destitute and starving. We have documents and newspaper accounts that show Georgiana and her friends helding fundraising balls for the destitute ribbon weavers to raise money, but also to raise the profile of their plight. They were called ribbon quadrilles. The ladies of society would purchase ribbons (Coventry ribbons of course) and decorate their dresses with them. Georgiana wore pink ribbons. For the exhibition Compton Verney commissioned the fabric designers Rapture and Wright to make a special fabric for the room which is called ‘quadrille pink’. It is based on an original Coventry ribbon design and we upholstered the chairs with it, as a tribute to Georgiana and her wider interests. I love the fact that she didn’t just have her head in a book, but was out doing things.

I love the fact that she didn’t just have her head in a book, but was out doing things.

You mentioned the six empty Victorian bookshelves. You decided that you were not going to just fill the empty shelves with books from the time. Why was that?

Compton Verney has 80,000 visitors a year, who are interested in many different things. Some visitors are interested in the amazing gardens or wildlife. And there are a lot of school visits and visitors who are children. We were interested in the fact that Georgiana was trying to say something through the medium of books, and I thought it would be interesting to find out what other people want to say with books – and particularly - to hear from certain reading communities who don’t get that much air space. This was the idea that excited us the most, and which we thought would work for our diverse audiences. We also wanted to make the exhibition as tactile and interactive as possible, so the more people we could involve in creating it, the better.

Who did you invite to curate the shelves?

We invited 6 guest curators (three individuals and three groups/institutions) - one for each of the empty shelves, to nominate books and to tell us why. The ‘why’ was important. I find it really difficult to ask people to do things, but it has struck me how immediately everyone very quickly said that they would love to participate.

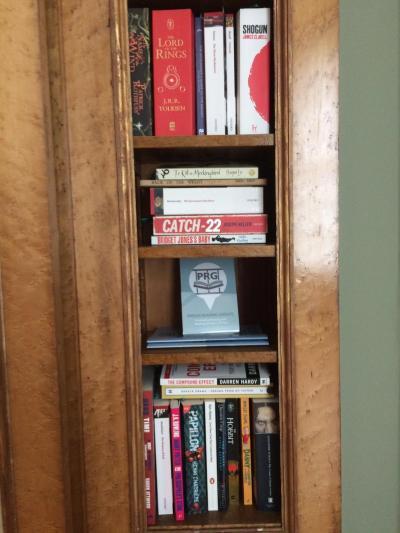

The first curator was really a no brainer. Emma Watson is an LMH Visiting Fellow, founded the ‘HeforShe’ campaign and launched her ‘Shared Shelf’ feminist book club, as part of the her work for the UN. I think subconsciously I was inspired by Emma Watson’s Shared Shelf when first thinking of how to curate the exhibition, since Georgiana’s imitation bookshelf is also a ‘shared shelf’ of a kind. So we were delighted when Emma graciously agreed to be a guest curator, and donated the books for her shelf.

The next shelf curator was suggested by Dr Eleanor Lybeck, who is also working on the project. She suggested gardener, writer and broadcaster Alys Fowler, especially since so many people visit Compton Verney due to its beautiful Capability Brown landscaped gardens. Alys very quickly said she would love to. There were two things she said had been crucially important to her in growing up. One was reading and the other was gardening. She curated a very personal selection of books for us, about coming of age, gender, the importance of nature and the environment, and what we can learn from it.

The third person we asked was writer and Pulitzer Prize winner Margo Jefferson. Last year I judged the Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction, and one of the shortlisted books was Margo Jefferson’s Negroland. It struck me as an amazing book. It is the story of her coming of age as part of a black upper middle class family in Chicago. A big part of the book concerns her reading. She writes about reading Ebony magazine, and thinking about the particular shade of one’s own skin, or reading Little Women and identifying or not with Jo March. The book also gives an amazing historic account of the way in which black Americans gained access to education, and to publication. She very quickly said yes to this project, and has written the most beautifully sparkling accounts of why books matter to her – from the copy of Alice in Wonderland that she read with her mother to the subtle writings of Nella Larsen and the poetry of Emily Dickinson.

We also involved three institutions. We asked for the participation of the local school, Kineton High School. This was crucial, not just because of Georgiana’s links with local schools, but also because the voices of year 7 and 8 students are not often heard. When we held workshops with the students, we felt it was important for them to know that there were no ‘right answers’. We didn’t want to hear what they thought they should read, but what they did read., Or to hear why they found reading difficult, or offputting. Their suggestions occupy one of our shelves. The students were also instrumental in talking to us about how the exhibition should be curated. They spoke about how important it was that books could be touched. The exhibition is supported by tablets in the room which allow visitors to find out the reasons why curators have chosen specific books. But the students at Kineton also thought of the idea of having bookmarks in the books with short descriptions of why they were chosen.

We also have a shelf curated by a charity called ReLit. ReLit is a charity that focuses on mental health and reading. I was one of the editors of an anthology of poems published by the charity. My fellow editors and I have suggested books for that shelf.

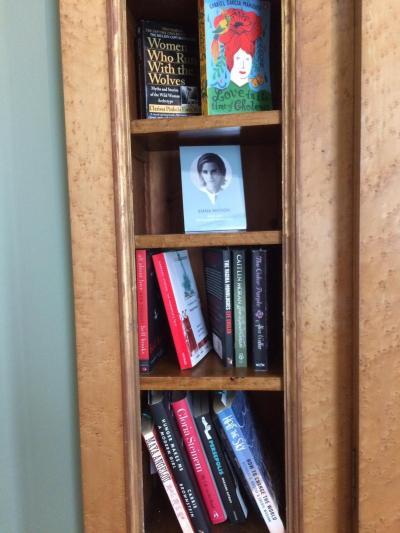

I love all the shelves, but the last one was perhaps the most startling and unexpected collaboration, because it was curated by members of prison reading groups. There is a charity - Prison Reading Groups - which has, for 20 years, facilitated reading groups in prisons. We were lucky enough to attend two of their reading group sessions and had the chance to tell them about the project. Men and women from prisons nominated books and told us why. Those are some amazing accounts of what books mean, and how books can be an escape of kinds. A quotation from that page on our website says ‘Reading changes lives, especially if you are in prison’. It so vividly showed how libraries matter. And coming full circle to what I said at the beginning of this conversation, walking through the strange environment of a prison, then reaching the warmth of a prison library really brought home to me what the presence of books can do, even if they aren’t being read.

In a world were books are increasingly digital, do we risk losing this physical experience of books and libraries?

I really hope that we don’t forget how important the library is as an affective space. A philosopher called Teresa Brennan writes about the idea of emotions as something we experience together. When I was in my teens I used to study in the local library, not because I needed to consult the books, but just to sit in what you might call a ‘held’ space. And there are so many stories that are there in a library space. Whether it is the story of the Dewey decimal arrangement or the idiosyncratic fact that someone has arranged all their books by colour, or the fact that it’s a mess…. You are getting some sense of another human being behind the design (or lack of it). There’s also the sense of being part of a tradition. The books have been there longer than you. Many people have passed through the space. There’s a sense of acknowledgment of the communal, of the shared.

One could also think about the importance of the book in its material form. Where a book is placed in a bookshelf sometimes creates stories for the future. Research projects have begun because of what was filed next to what. Or what about how the material feels, and how it has been touched, or doodled upon? When I was researching for my recent project on Dickens, I realized that these fragile pamphlets – his weekly ‘numbers’ only survive because people cared about them . People collected them, ready to lovingly get them bound up into a complete book. So when you go to the Bodleian to look at a rare collection of The Old Curiosity Shop in its weekly or monthly form, you are also looking at the record of someone else’s stewardship, at the way in which someone has touched and held something over time. It’s like if you lose a book that you’ve loved reading, you could buy another - identical - copy but it is not the one you had held before. And there is also that sense of the shared touch in a library. Other hands have touched these books, and there is something connecting about that possibility.

We hope that people who come Compton Verney have that sense of the community of people coming and going and passing through the room. We are also converting the whole exhibition into book form so that it can be sent back to the prisoners (who do not, of course, have access to the internet) so that they can have a printed copy of the virtual exhibition. We hope that that they get a sense of the book that has been touched by us - and that this will go back to them, to show how they have touched us with their stories.

Other hands have touched these books, and there is something connecting about that possibility.

What do you hope people will take from the exhibition?

I hope that people will see this - in its real and virtual form - as a celebration of why and how books matter. I hope it will also illuminate the richness of studying literature. When I say ‘I teach literature at University’, people often think that means reading the words in hard or paperback books. And sometimes it is. But I hope this exhibition will allow people to think about studying literature in a different way. There are many resources on our website about the history of the book, about reading and illness, reading and costume, it shows that the study of literature is also the study of anthropology, psychology, art history… so I hope it will provide some access into the really exciting and fun research we are doing here at Oxford.

We also developed some great workshop ideas that I hope will be a good resource to schools, which I’d love to develop into kits. I hope that there will be something on the shelves for each person, from Alys Fowler’s shelf about the natural world to the snapshot of what eleven and twelve year olds read. And I hope people will find the particular story of this one woman, Georgiana Verney, interesting. Virginia Woolf said “Why should a life be seen to more commonly exist in that which is large than that which is small?”. The story of the Women’s Library at Compton Verney connects with the big picture of women’s rights, but it’s also the history of one life, that of Georgiana Verney. It is quite inspiring to think that what you might decorate your sitting room with, might be the foundation of an exhibition one day!

As part of this project you organized a series of workshops with the local school, including a workshop at LMH. Can you tell us more about it?

We held a workshop at Compton Verney for Kineton High school pupils called ‘Selfies versus Shelfies’. I tried to think about ways in which we could explain the relevance of imitation books - and to make the idea of that space can tell stories - accessible to 12 year olds. Compton Verney is filled with amazing portraits, and it struck us that there was a felicitous coincidence between Georgiana’s ‘shelfie’ and the idea of the portrait, or ‘selfie’. We began our workshop by thinking about famous selfies, and how students would portray themselves if they had to take a photograph. What would they be wearing? How hard would it be to portray their true self? Many of them said they would be up a tree or in football kit, rather than school uniform. We then went around the galleries and looked at the portraits as ‘selfies’ and representations of self. Finally we went into the Women’s Library and the students acted as detectives. They spotted the imitation spines and we discussed why Georgiana would have put them there. This then evolved into a discussion of how houses can tell clues about who we are, and how we express ourselves not just through our bodies but also our lived environment. This workshop was then followed by a book sculpture workshop here at LMH, where we shocked a lot of people by chopping up books to make pieces of art!

Last week you were awarded an Oxford University Public Engagement Award for this project. What does this prize mean to you?

It was wonderful that our team at Oxford were recognized by the Vice Chancellor’s Awards. It really has been a hugely collaborative project – the Oxford Team and the team at Compton Verney – so it was a celebration of that. The judging panel particularly picked out the fact that this was an ‘innovative’ way to engage the public. For me personally, in research terms, I’ve always followed my instincts, and liked thinking creatively, but felt a bit unconventional in my approach. And that can, at times, make you feel out on a limb. So I’ll take the award as a reminder that unconventional is good, and to keep working in this way!

Find out more

Unsilencing the Library can be visited at Compton Verney Art Gallery and Park in Warwickshire, or online on this website.

Visit Dr Sophie Ratcliffe's page to find out more about her research and career. More information on studying English Literature at the University of Oxford and Lady Margaret Hall can be found here.

Imitation book shelf photo by Deborah Longworth. Curated book shelf photos by Elaine Mitchell.