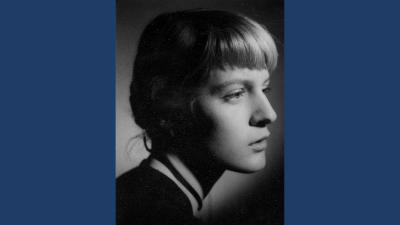

As remembered by Gillian Tindall FRSL (1956-59)

When I arrived at LMH, exactly one year after my mother's abrupt death and a matter of weeks since my father's re-marriage, I was struck by how nice everyone was.

After a childhood that had included a 'progressive' school so way-out that it resembled a hippy-commune, before these had been invented, and also a girls' boarding school of deadening intellectual mediocrity and confinement, plus several months alone in Paris during which I perforce acquired both French and assorted adult experiences – well, after all that, the college struck me as something of a rest-cure and haven. I was mildly amazed that many of my contemporaries seemed to find it exciting, daunting even!

Everyone – dons, scouts, lecturers, even most of the young men who were eager to take one out for the evening (grown men themselves, actually, since in my year they had nearly all done National Service, usually as officers) - were polite and generous. The men could not, in any case hope to wheedle their way in for the night, since LMH only admitted male visitors from 2pm to 7pm.

I do recall less fondly, however, just one person – the then Bursar. I have forgotten her name, which is just as well. I know that in the all-male colleges that made up most of 1950s Oxford, Bursars handled finance and were persons of knowledge and influence. However, it seems to me that at LMH at that time the job was more that of a house-keeper. Probably it is different now.

Anyway, this Bursar appeared to be responsible for, among other things, the quality of the electric light in the individual rooms, a not-unimportant matter when, as now, essays were often written through the night. And in Old Hall, where I spent all my three years because I liked its surviving old entrance and big rooms, the lights were not great. As a hang-over, probably, from some wartime economy, the switches were so fixed that you could have on the centre light or the desk lamp but not both at once. Since the bulb provided in the centre of my room was only 40W and that in the lamp only 60W, this seemed to me inadequate.

So I had a little moan about this in the JCR book for 'suggestions' which, as is the nature of things, were often mild complaints. (Does a JCR book exist now, I wonder?). To my shocked contempt, instead of recognising that the complaint might have some merit, the Bursar responded that since 60W plus 40W make 100, that should be adequate. Quite apart from the scientific ignorance of this remark, she must have known perfectly well that one couldn't put both lights on together. So, in my written response to her I made it clear what I thought of her logic, let alone her unconcern for the students' eyes, no doubt expressing myself more rudely than I would now. The Bursar responded further by writing that she had never been so insulted in her life!

(Which I hardly feel could have been true. If so, she must have led a remarkably sheltered existence).

Nothing more came of this, that I am aware, and she and I avoided each other mutually from then on. It is possible that a don had had a word with her. I solved the problem (and encouraged friends in neighbouring rooms to do the same) by buying a 100W bulb for the desk lamp, which for a little while I took out each morning and stuck in a drawer, just in case the scout for that floor might have been told to remove such a device! In practice, our scout was perfectly nice and I think would have had more sense.

The Bursar's behaviour, redolent of a really bad boarding school, shocks me now if anything still more than it did sixty-five years ago. But since that is literally the one single example I can recall of bad management in the college, it shows how extremely well run it was in every other way. Strange to realise that this was at a period as distant from us now as we were distant then, in the late 1950s, from the college's first opening in Norham Gardens with a mere handful of girls!