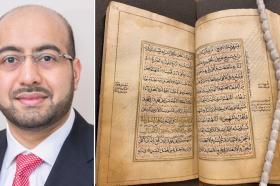

A true polymath, Gulamabbas Lakha (2014, MPhil Islamic Studies and History) read economics and econometrics as an undergraduate before completing four masters degrees spanning theology, religion, Arabic, history, psychology and neuroscience. While serving as CEO of the investment firm he founded, he is also a DPhil candidate at Oxford’s Department of Psychiatry. Gulamabbas explains how he is using his diverse experience to consider how faith-based practices can support treatments for mental health problems, particularly in Muslim and other faith communities.

Finding inspiration

It was the death of his father, Gulamabbas says, that guided him towards the wide-ranging academic path he has followed ever since. “My father passed away in 2010, having been a pivotal figure not just in my personal development, but in my intellectual development. He was a barrister but had managed for many years to juggle this with his ministry in the Muslim community. He was a good example of how it was possible to balance a professional career and a ministry vocation.”

His father had been due to deliver a sermon at their local mosque, and Gulamabbas was asked whether he would be willing to speak instead. “I felt completely underqualified,” he admits. “The only thing I was qualified to do was economics. But I didn’t want that one last obligation to go unfulfilled, so I said yes. And I basically narrated, almost verbatim, a previous sermon I had heard my father deliver. It was about the daughter of Prophet Muhammad, Lady Fatima, regarding a set of teachings on practical psychology and how to live with people who disagree with you.”

Looking back, Gulamabbas sees this period both as a turning point in his professional life and as an early indicator of his ongoing fascination with the interaction between faith and mental health. Having focused on economics as an undergraduate, he had become a chartered financial analyst and gone on to set up an investment management company. But as Gulamabbas considered his father’s legacy, his own ambitions, and his passion for pursuing academic research with practical applications – which emerged from two decades of business and community work – the draw of further study became irresistible.

As such – and in a move he is quick to say “would have been impossible without all kinds of support from my family” – he came to Oxford to study for a PGDip in Theology, together with a Masters in Islamic Studies from the Islamic College in London, followed by an MPhil here at LMH, focused on Islamic Studies and History.

Reassessing the Psalms

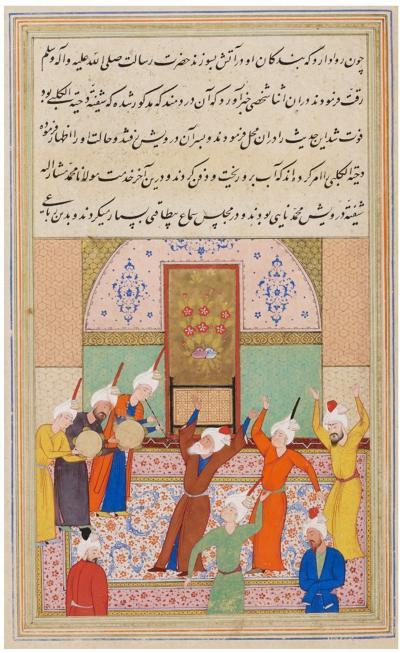

While at LMH, Gulamabbas began using early Arabic primary sources to investigate the reception given to Al-Ṣaḥīfa al-Sajjādiyya, one of the oldest Islamic prayer manuals. This included analysing commentaries that had not previously been studied in Western scholarship. Several reinforced Gulamabbas’s own experiences of the text’s psychological significance. “In my own personal journey,” he says, “I had always been really struck by the power of psalms. They had helped me in periods of darkness, loneliness, fear and anxiety. As a young student I remember I had a CD of psalms that I would listen to and all the knotted-up emotions – uncertainty, self-doubt – would feel easier to process. I would finish feeling grounded and empowered.”

“The psalmists had the ability, through their knowledge of theology and mastery of language, to present an array of mirrors at the right angle to shine a light on that which I couldn’t or didn’t want to see about myself,” Gulamabbas reflects. He continues, “What I discovered looking at the earliest reception history of this text was that 400 or 500 years ago, scholars were much more in touch with this same idea of practical psychology. I think in more recent years Islamic scholarship has become more juristic, but in the earlier era, scholars of Islamic law were also mystics and philosophers, what today we would call ‘multi-disciplinary researchers’, and were more willing to discuss psychological dimensions of religious texts.”

Bolstered by his findings, Gulamabbas became increasingly interested in how faith-based concepts and practices can support mental health. He continued his studies with a Masters in Psychology, with a large neuroscience component. For his thesis he undertook a brain imaging study to compare EEG neural correlates [the association between a physical occurrence in the nervous system and a mental state or event] of a secular and Islamic mindfulness practice. Having reached a point where he felt confident combining what he calls the “theological and empirical” aspects of his studies, he began his DPhil in Psychiatry within the Neuroscience, Ethics and Society (NEUROSEC) team here in Oxford.

Breaking through stigma

One issue that has been at the forefront of Gulamabbas’s thinking is how to overcome the stigma linked to mental illness, particularly in Muslim communities. Following religious training over a number of years, he was accredited as a Shaykh and has been lecturing on contemporary Islam at mosques across the UK and on Muslim TV channels over the last decade. “Sometimes from the pulpit,” Gulamabbas says, “the stigmatising myth is presented that mental health challenges, whether anxiety, depression or other conditions, are somehow a manifestation of poor faith. There’s an idea that if you had stronger faith, you would not be experiencing depression or anxiety, that if you trusted God more, you would not be anxious or depressed.”

“I have always wanted to dispel that myth, because mental health challenges are a feature of human experience, just like physical health challenges. For instance, if someone walked into a mosque with a crutch, would your first instinct be to offer them a chair or kick the crutch away? Because what you’re really doing by stigmatising mental health is adding a layer of guilt on top of the existing depression or other condition. This leads me to think about how faith could and should instead play a role in supporting mental health.”

“If we look at the Qur'ān,” Gulamabbas adds, “there are examples of eminent prophets – Jacob, for example – who experienced various challenges. At one point, when Joseph was lost in the desert, the Qur’ān says Jacob’s eyes turned white with grief. And yet, Jacob speaks lucidly in that chapter about the importance of maintaining hope and optimism in the face of adversity, and not allowing negative experiences to sacrifice our optimism. I see links there with modern therapeutic interventions, such as mindfulness and cognitive behavioural therapy, enabling people experiencing depression and anxiety to perceive their experiences differently. You could say optimism and hope are the building blocks of both spirituality and psychotherapy.”

Creating a faith-based framework

Such thinking is at the heart of Gulamabbas’s current research focus – the development of what he calls a Faith Informed Therapy framework. His DPhil takes a multi-disciplinary approach to investigating how religious concepts and practices can be harnessed for psychotherapeutic purposes among faith communities, focusing on depression within the UK Muslim population. His work is both conceptual and empirical, building a bridge between service providers and service users. The potential impact, Gulamabbas explains, is wide-ranging, with scope for improving accessibility to therapy among minority communities with high levels of mental illness. It could also enable clinicians from a range of backgrounds to provide more personalised mental health care at low cost.

The conceptual part of Gulamabbas’s thesis identifies ten psychotherapeutic techniques from NICE [National Institute for Health and Care Excellence] guidelines for treating depression – five relating to metacognition (or managing thinking patterns) and five related to building resilience (by focusing on concepts including gratitude and motivation). It maps these on to well-established concepts and practices in Islam, such as daily prayer, scripture, fasting, mindfulness and psalms.

Of his empirical research, Gulamabbas says, “My learning from both patients and clinicians has been that if NHS-approved interventions for depression, such as cognitive behavioural therapy, mindfulness and behavioural activation, were presented using Islamic concepts and practices, it could make them easier to access, as the stigma associated with psychotherapy could diminish and there may be more trust in the whole process. Secondly, adherence to therapy could improve, as psychotherapeutic techniques could be linked to habits and practices that are already established.” The practical application of his work has already attracted attention from community groups as well as professional organisations, such as the World Psychiatric Association. More recently, the Department of Psychiatry at Oxford conferred on him a Race Equality Recognition Award in acknowledgement of the impact of his research.

Gulamabbas is keen to share what he has learned, serving as a tutor in Psychology of Religion and leading seminars on the Neuroscience of Religious Experience, alongside his supervision of medical students and postgraduates. He lectures on Christian-Muslim relations, co-founded the Oxford Interfaith Forum and has led Bodleian Library public workshops on psychotherapy in the Hebrew Old Testament and Arabic Islamic psalms.

Gulamabbas is clearly excited at the opportunities he is identifying to link therapy and faith, not least because it feels as though they mark the natural culmination of many years of study. “What inspires me about my work is building bridges,” he says. “But the challenge with building bridges is you need to understand the lay of the land on each side – patients and clinicians – so you need to speak the language that is spoken on each side, theological and scientific. Whilst being in a position to communicate with both groups is a privilege, it also brings considerable responsibility to create meaningful positive impact for both communities.”

This article first appeared in LMH News 2024. You can read the full issue on our publications page.

Find out more

Read more about Gulamabbas’s research on the Department of Psychiatry’s website.

Image: Illustration of a Ṣūfī meditative spiritual concert (samāʿ). Source: Oxford, Bodleian Library MS. Ouseley Add. 24 (1552); fol. 119a