Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary (1755) was not, as is often supposed, the first comprehensive dictionary of the English language. In 1604, schoolmaster Robert Cawdrey published his Table Alphabeticall, a list of around 3,000 words, drawing on earlier school texts and studies of the language. LMH Library holds a 5th edition of the first book to call itself a dictionary, Henry Cockeram’s English Dictionarie, also known as:

An interpreter of hard English words: Enabling as well ladies and gentlewomen, young schollers, clerkes, merchants; as also strangers of any nation, to the understanding of the more difficult authors already printed in our language, and the more speedie attaining of an elegant perfection of the English tongue, both in reading, speaking, and writing.

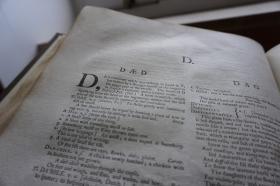

But it is Johnson’s Dictionary that is the most famous, and LMH is home to a 2nd edition of the mighty work, in two volumes. The book was larger and more comprehensive than any that had gone before it, containing over 40,000 words, and covering every branch of learning from agriculture to zoology. It was especially notable for its novel use of literary quotations to give context to a word’s usage: the nearly 115,000 extracts draw especially on Johnson’s favourite authors (Shakespeare, Milton, Dryden) – ‘the best writers’, as he calls them on the title page – some of whose lines, in the spirit of the age, he revised if they failed to meet his exacting standards…

Though it was a commissioned work, Johnson’s Dictionary was soon bent to its compiler’s will. In its preface, he quickly established his guiding principles:

[A]cademies have been instituted, to guard the avenues of their languages, to retain fugitives, and repulse intruders; but their vigilance and activity have hitherto been vain; sounds are too volatile and subtile for legal restraints; to enchain syllables, and to lash the wind, are equally the undertakings of pride, unwilling to measure its desires by its strength.

However much Dr. Johnson the scholar would’ve liked it, Samuel Johnson the author knew his book could only be a pin in the map of an ever-changing English language; he defined the ‘lexicographer’ as ‘a harmless drudge, that busies himself in tracing the original, and detailing the signification of words.’

The LMH copy was rebound in the 20th century, but is otherwise in excellent condition. It, along with many other 16th-, 17th- and 18th-century books, is available for consultation by internal and external readers in the Briggs Room of the Library: just email librarian@lmh.ox.ac.uk.