The results of their experiment, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), could offer new insight into the long-standing mystery of the Universe’s hidden magnetic fields and missing gamma rays.

Blazars are active galaxies powered by supermassive black holes that launch narrow, near-light-speed beams of particles and radiation towards Earth. These produce intense gamma-ray emission, detected by ground-based telescopes, which should generate cascades of electron-positron pairs as they travel through intergalactic space. Those pairs are expected to scatter light again to create lower-energy gamma rays which should be detectable by gamma-ray space telescopes such as the Fermi satellite - yet these have not been observed.

One explanation is that the pairs are deflected by weak intergalactic magnetic fields, steering the lower-energy gamma rays away from our line of sight. Another hypothesis, originating from plasma physics, is that the pair beams themselves become unstable as they traverse the sparse matter that lies between galaxies. In this case, small fluctuations in the beam drive currents that generate magnetic fields, reinforcing the instability and potentially dissipating the beam’s energy.

To test whether plasma instabilities could be disrupting the particle beams, the team used CERN’s HiRadMat (High-Radiation to Materials) facility to generate electron–positron pairs with the Super Proton Synchrotron and send them through a metre-long ambient plasma, creating a laboratory analogue of a blazar-driven cascade propagating through intergalactic plasma. Contrary to expectations, measurements showed that the pair beam stayed narrow and nearly parallel, with minimal disruption or self-generated magnetic fields. When extrapolated to astrophysical scales, this implies that beam-plasma instabilities are too weak to explain the missing GeV gamma rays, supporting the idea that the intergalactic medium contains a magnetic field that is likely to be a relic of the early Universe.

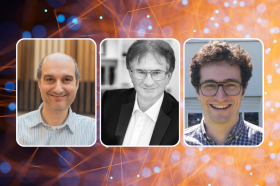

Professor Gregori said: “Our study demonstrates how laboratory experiments can help bridge the gap between theory and observation, enhancing our understanding of astrophysical objects from satellite and ground-based telescopes. It also highlights the importance of collaboration between experimental facilities around the world, especially in breaking new ground in accessing increasingly extreme physical regimes.”

Dr Bilbao added: “For a theorist, it’s extraordinary to see experiments now confirming and extending ideas that, until recently, existed only in simulations. These results show the power of combining large-scale computation with world-leading experimental facilities like CERN to probe the physics of cosmic plasmas.”

Reflecting on the interdisciplinary nature of the work, Professor Huffman said: “My research is normally in the study of Higgs bosons at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, but I came to understand Gianluca and Pablo’s research both through the natural way researchers from all fields can interact in Oxford colleges and through one of our former LMH students (and Gianluca’s Graduate student), Charles Arrowsmith; the lead author in this work.”

The team’s findings, however, bring up more questions. The early Universe is believed to have been extremely uniform and it is unclear how a magnetic field may have been seeded during this primordial phase. According to the researchers, the answer may involve new physics beyond the Standard Model. The hope is that upcoming facilities such as the Cherenkov Telescope Array Observatory (CTAO) will provide higher-resolution data to test these ideas further.

This collaborative effort involved researchers from the University of Oxford, STFC’s Central Laser Facility (RAL), CERN, the University of Rochester’s Laboratory for Laser Energetics, AWE Aldermaston, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics, the University of Iceland, and Instituto Superior Técnico in Lisbon.

The study, ‘Suppression of pair beam instabilities in a laboratory analogue of blazar pair cascades’ has been published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).