For five years, Pauline Baer de Perignon (1996, MSt European Literature) searched for answers that would reveal what happened to renowned artworks collected by her great-grandfather, Jules Strauss. The resulting book – The Vanished Collection – builds a bridge between Nazi-occupied France and the present day, and combines family history with deeply personal insights into generational trauma and looted art.

Below, you can read the story of Pauline’s journey to uncover the fate of her family’s looted artworks in an article taken from the 2023 edition of LMH News.

The beginning of a journey

Pauline Baer de Perignon’s investigation into the fate of Jules Strauss’ art collection began at a concert by Caetano Veloso, the pioneering Brazilian musician. It was 2014, and her cousin, Andrew, leaned towards her and suggested there could be ‘something shady’ about the sale of Strauss’ celebrated art collection, more than 70 years earlier. The pair met again shortly afterwards, and Andrew presented Pauline with an astonishing list of paintings that had been declared stolen, having once been owned by Strauss. It included three by Degas, four Renoirs, two Sisleys and two Monets.

In the months and years that followed, Pauline immersed herself in research to try and unravel and understand what had happened to her great-grandfather’s collection during the Nazi occupation of France. Her enquiries took her across Europe and added a new dimension to many of her family relationships. “It began with curiosity about my family and about art and French history,” says Pauline, who now lives in Paris but returns often to Oxford – a city she adores. “There was a mystery, an enigma, and that was fascinating to me. I’ve always loved mysteries and delighted in searching for the truth within my family – to uncover the post-war silence and better understand my origins.

“I reached a turning point,” she adds, “where I discovered the injustice in this story. I wanted to uncover this and I had a feeling I could do something for my family.”

A quest for repatriation

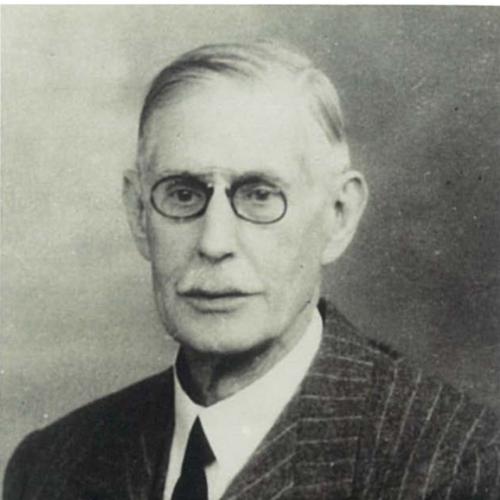

It is estimated that the Nazis looted some 600,000 paintings from Jews during World War II, of which at least 100,000 are still missing. The practice was intended both to enrich the Third Reich and to eradicate Jewish culture. Before the outbreak of war, Jules Strauss had been a well-known Paris collector, who loved French 18th century art, and in particular the French Regency style. He lived among the furniture, ornaments, paintings and drawings he accrued and, though he remained in Paris during the war and avoided deportation, Pauline’s research raised many questions about whether Jules’ art was either stolen or he was forced to sell.

The strain he was placed under undoubtedly took a terrible toll. Jules lost his son, André, during the War and Pauline found evidence during her research that his home was expropriated. As the catalogue to a 1961 sale of Strauss’ art explains: ‘The collection never stopped growing and, during the terrible years of the Occupation, it was a difficult task to keep all these objects safe. Distraught in the wake of his son’s death, harried by persecution, devastated by the tragedy that had befallen his country, Jules Strauss died in 1943.’

Curiosity, not revenge

Pauline’s approach to seeking out the truth was, by her own admission, entirely unstructured. “I started by looking into everything all at the same time,” she smiles. “I made lists of artworks that had belonged to Jules and went through auction house archives to try and find out who’d bought and sold them. I wrote to everyone – academics, art historians, researchers... My method was that I had no method.”

She believes, however, that her inexperience worked to her advantage. “It was helpful for me to be so naïve at the beginning,” Pauline says, “because if I had known more, I wouldn’t have dared to have bothered all these people. And people were very helpful, actually, because I think they could feel I was quite curious but in a good way.

“I remember talking to someone who told me that this kind of search and investigation has to be done with no anger against history or against people. It has to about seeking the truth, but with no idea of revenge.”

Pauline’s research rapidly became an obsession. She spent day after day in the research rooms of the Musée d’Orsay and the Louvre and at the French Foreign Ministry’s Diplomatic Archives Centre, scouring art catalogues and articles. She discovered that her great-grandmother did file a report of painting theft in Paris after Jules’ death. This leads her to reflect deeply on why this chapter of her family’s history, and her Jewish identity, was so little discussed in the decades that followed. As a result, her book becomes as much a study of collective memory and the need to forget as the story of an investigation. “People had gone through so much loss. Family loss, lifestyle loss, art loss,” Pauline says. “The War was the end of people’s beliefs, the end of joy. People had to change everything afterwards, and I think that’s why it wasn’t easy to talk about it.

“I can’t repair that sadness and trauma,” she adds, “but recovering memories and finding the truth matter. In situations like this, they are among the most important things you can do.”

The battle for justice

Pauline calls her investigation a sentimental journey. “You get very close to people you’ve never met”, she says, describing what it meant to build a growing picture of this hidden period in her family’s history. “I felt that Jules was holding my hand during my research and I got to know him and my great-grandmother. It was really helpful, because research can be a lonely process.”

As the years went on, the many hours spent alone in archives began to pay dividends. Pauline travelled to Koblenz in Germany and, despite a range of frustrations – the archive had not been digitised, the language barrier prevented her from understanding the classification system, even her Airbnb apartment had been double booked – she found a key piece of evidence. It was a receipt, showing that a drawing by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, ‘A Shepherd’, had been sold to the Nazis. A short while later, she discovered that this painting had been listed as missing from Strauss’ collection. It was the kind of proof she had been seeking all along.

At this point, Pauline began to encounter another challenge that required all of her resolve and analytical nous– appealing for artworks to be returned. She discovered that the Tiepolo drawing was now held by the Louvre. Documents there show that Strauss – a major donor to the Louvre during his lifetime – had owned it before the war. She began to question whether, ‘the museum, which had been holding on to the drawing for 70 years, had no intention of returning it’.

Further painstaking research then revealed that ‘Portrait of a Lady as Pomona’ by Nicolas de Largillière, at the time housed in the Old Masters Picture Gallery in Dresden, also once belonged to Jules Strauss, before ending up in Nazi hands. Pauline travelled to the museum in Germany to ask for its return and was met with a response she says left her “speechless”. The museum’s director suggested that Strauss may have been ‘happy’ to sell his painting in the 1940s. The anger and upset Pauline felt penetrates the book at this stage, as it does when the museum later suggests that it will return the painting – but only if Strauss’ ancestors then sell it back to the museum. As she writes, ‘restitution is a way of acknowledging persecution’ – and she was not willing to have conditions attached to it.

In the end, some version of the justice Pauline had always been searching for was achieved. Staff at the Louvre proved accommodating to her requests, and the Tiepolo was returned to Pauline and her family at a ceremony in the French Ministry of Culture. Then, in January 2021, 80 years after the painting was first appropriated and more than four years after Pauline began appealing for its return, the Largillière was returned to France. With pandemic restrictions still in place, the painting was carefully carried into Pauline’s home. She and her husband, Henri, stood looking at it in silence for several minutes, both still wearing the facemasks they had put on during the delivery, both thinking of the journey it had taken and what that journey represented.

A journey towards acceptance

The Vanished Collection is many things. It reads at times like a detective story and at others like a family history, but one with far-reaching and wide-ranging consequences. But it is notable throughout for being a search not only for truth but also for purpose. ‘What I wanted to say,’ Pauline writes, ‘was that, at last, I had achieved something with my life.’

“That is my character,” she adds today. “Educated as a girl in bourgeois society, it’s easy to think you’re not really worth anything. I knew I had always dropped things easily or discouraged myself. That was no longer the case.”

Pauline is now considering what comes next. She has stopped spending whole days and weeks in archives, and has no intention of trying to locate all of the artworks that once took pride of place in her grandfather’s collection. She may write a new book, she says, based on conversations with others who have faced similar challenges to her own.

But, whatever the future holds, it is clear that the labyrinthine journey that began at a Caetano Veloso concert has had profound consequences for Pauline’s family, her history and her own sense of self. “I was always searching for something,” she says, “and this gave me that purpose. It gave me a reason to be proud.”

About the book

The Vanished Collection: Stolen Masterpieces, Family Secrets and One Woman’s Quest for the Truth is available now, published by Head of Zeus. A review of Pauline’s book was published in the 2022 edition of The Brown Book (p.144).